Commemoration for George Brown (1906-1937). Inistioge, Co. Kilkenny (Ireland)

- George Brown and the defence of the Spanish Republic by © Manus O’Riordan

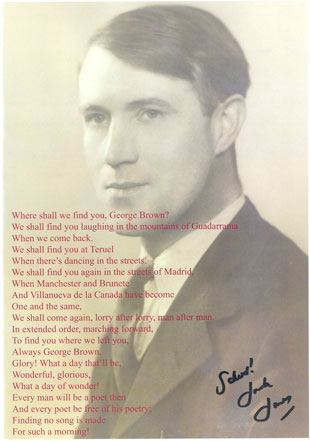

- Poster Commemoration

- Press: Commemorating a truly international volunteer army, published by © Waterford Today, 25/06/2008: Download file [.pdf]

- Press: Honouring an heroic history on the memorial ceremony for brigadier George Brown, published by © Pauline Fraser to Morning Star, 23/07/2008: Download file [.pdf]

- Press: Spanish war hero remembered by Damien Tiernan correspondent, © RTÉ News, 30/06/2008: http://www.rte.ie/news/2008/0628/6news.html

- Commemoration Photos

George Brown and the defence of the Spanish Republic

by Manus O’Riordan, Executive Member for Ireland International Brigade Memorial Trust and SIPTU Head of Research.

The 1st George Brown Memorial Lecture delivered in St. Mary’s Church of Ireland Inistioge, Co. Kilkenny 27 June 2008

INTRODUCTION

On 27th and 28th June 2008 the Inistioge George Brown Memorial Committee held a weekend of commemorative events in that South Kilkenny village that lies between Thomastown and New Ross, Co. Wexford. Six months previously, on 30th December 2007, the Committee had dedicated an Olive Grove in Woodstock Gardens and unveiled the following Memorial Plaque:

NO PASARÁN

NO PASARÁN

THIS OLIVE GROVE IS DEDICATED

TO THE KILKENNY MEMBERS OF

THE 15TH INTERNATIONAL BRIGADE

WHO FOUGHT IN DEFENCE OF

THE SPANISH REPUBLIC 1936-1939:

GEORGE BROWN (KILLED IN ACTION MADRID 7-7-37)

MICHAEL BROWN

MICHAEL BRENNAN

SEÁN DOWLING

UNVEILED 29-12-07 BY PÁDRAIG Ó MURCHÚ, INISTIOGE.

A memorial booklet was compiled, edited and designed by Committee member Terry Bannon, and entitled “George Brown 1906-1937: Working Class Activist and Member of the XV International Brigade in the Spanish Civil War”. This booklet was launched by Bob Doyle, the last surviving Irish member of the Fifteenth International Brigade, in St. Mary’s Church of Ireland, Inistioge, on 27th June 2008.

Joe Doyle, Chairman for the evening’s events and PRO and Treasurer of the George Brown Memorial Committee, thanked the Church of Ireland community in Inistioge for the use of their place of worship over the two days of the commemoration, where indeed some of George Brown’s own ancestors would themselves have worshipped. Still more of Brown’s ancestors would have worshipped in the adjacent Catholic Church of St. Colmcille. The Brown family graves are in the cemetery that adjoins both churches and which has long been shared by both the Catholic and Protestant communities of Inistioge. A Memorial Plaque to George Brown himself would be unveiled on the following day by his fellow International Brigader Jack Jones on a cemetery wall facing those same Brown family graves.

Chairman Joe Doyle alluded to some of the Church’s own memorial plaques and how some things never change, with one plaque commemorating a 19th century military death in the Afghan capital of Kabul. But another thing that also has never changed is the life-long commitment of International Brigader Bob Doyle (no relation) to struggles of a different kind. He therefore called upon Bob to launch the George Brown Memorial Booklet.

ADDRESS BY BOB DOYLE

We are here today to honour George Brown and the many others from Ireland and other countries who went to Spain to fight Fascism. As the last Irish soldier of the International Brigades, I am honoured to open this commemoration in his native county.

I was born in 1916 in the Dublin slums, and joined the IRA in my teens. In 1934 I left the IRA to join the Republican Congress set up by Peadar O’Donnell, Frank Ryan and Kit Conway. The time had come to support the fight of tenants against landlords, of workers against anti-union employers, and to take on the Blueshirts in the streets. We were still Republicans, but now we were social revolutionaries also.

Had we stayed in the IRA as it was then, many of these employers and landlords would have still supported us and the IRA’s purely nationalist policies. We had to form coalitions with groups who might have differed from us in the past but now shared our campaigns for social justice and fighting the rising tide of Fascism.

In 1936 we realised that this struggle was being fought even more critically elsewhere, especially in Spain. This is what led me and my ex-IRA comrades to join the International Brigades. We were with volunteers from 53 countries who also saw that their fight was the same as the Spanish people’s: our slogan was “Bombs on Madrid mean bombs on London” and as I saw for myself, this slogan was proved all too true.

With the betrayal of the Spanish Republic by Britain’s Tory Government and their French and American allies of big business, Hitler, Mussolini and Franco won the war in Spain. Six months later the Second World War began, and bombs began to fall on cities everywhere, as they still do today.

Yet despite the Allied victory in 1945, we now find that Fascism, raw Capitalism, is thriving, and using spin doctors instead of the old racist speeches, while more powerful weapons are being developed, supposedly to protect us, and our environment is in crisis. This crisis cannot be solved by Capitalism, because Capitalism is now its cause.

My generation’s vision of a world without exploitation, where we live in harmony with our environment, seems as distant as ever, while Globalisation, which is the worldwide triumph of money over organised workers, undermines our democracies. The fight today is as vital as it was in Spain, but remember we are fighting for an idea, and though we must at times defend ourselves, guns cannot impose an idea: the four weapon of victory today are – Education, Organisation, Civil Disobedience and Unity.

From my lifetime of struggles, these are the lessons which I have learnt. Take up the fight, and let us fight together, for the Liberation of Mankind. La lucha continua.

VIVA LA REPUBLICA!

END

The Chairman next called upon Manus O’Riordan, SIPTU Head of Research and Executive Member for Ireland of the International Brigade Memorial Trust, to deliver the first George Brown Memorial Lecture.

LECTURE BY MANUS O’RIORDAN

A Chathaoirligh, a chomrádaithe agus a cháirde,

It is indeed a great honour to be delivering the first George Brown memorial lecture here in Inistioge this evening. Little did I then know – when I was a young teenager present in Croke Park in both 1963 and 1969 to see Kilkenny’s illustrious and outstanding hurler Eddie Keher win two of his six All-Ireland Championship medals – that I would have occasion to be speaking here in Eddie’s own home village four decades later! Still less did I know that, through my future wife Annette, I would acquire in-laws in this locality, the Hennessy family of Glensensaw. And it was beyond all foreknowledge that, as the son of an Irish International Brigader here to honour his fellow Brigader George Brown, I would in fact also be honouring a close relative of that self-same Eddie Keher [a first cousin, once removed: George Brown’s father was the brother of Eddie Keher’s maternal grandfather].

It is a particularly great privilege for all of us on this commemorative occasion to be in the presence of Jack James Larkin Jones, President of the International Brigade Memorial Trust. Jack had become a good personal friend of George Brown and his newly-wedded wife Evelyn Taylor – a courageous anti-Fascist activist in her own right. George Brown married Evelyn as he set out for Spain in January 1937, and she would never again see him before he was killed in action six months later. At that time that other young activist, Liverpool’s own Jack Jones, was to the fore in campaigning for solidarity with the Spanish Republic in the year before he himself would also set out to fight in the ranks of the International Brigade. In his recently republished autobiography, “Union Man”, Jack recalls:

“In this period I met again Evelyn, whose husband, George Brown from Manchester, had been killed in Spain at the Battle of Brunete. She had been working abroad, in the underground movement against Fascism, and had taken many risks in doing so. The death of George was a deep personal wound which only time could repair, yet her mood was not to grieve but to fight on. My admiration for her spirit was more than matched by my growing love for her. We both knew, without putting it into words, that if I returned from Spain we would marry.”

Jack Jones fought alongside my own father Michael O’Riordan in the 1938 Battle of the Ebro, where they were both wounded. Following his return from that war, Jack and Evelyn were indeed married and went on to share a lifetime of love, comradeship and struggle, until Evelyn’s death ten years ago. I am, therefore, extremely delighted that among the Jones family party present here with us this evening are the two sons of Jack and Evelyn, Jack Jnr and Mick.

Jack Jones celebrated his 95th birthday last April, and beside him that other International Brigader who honours us by his presence, Dubliner Bob Doyle, is a mere kid at 92! Five years ago, when the third last surviving Irish International Brigader Eugene Downing passed away, my own father and Bob began to joke with each other about competing in some sort of slow bicycle race as to who would go down in the history books as the very last Irish International Brigader. When my father came to terms with his own approaching death in May 2006, and began to say his goodbyes to us, he also added:

“Good luck to Bob Doyle – he’s the last man standing!”

And so it was – when speaking a month later at the launch of Bob’s autobiography “Brigadista” – that I introduced myself as the son of the runner-up!

I am very pleased that so many deceased International Brigaders are represented by family members at this commemorative weekend. My own father is additionally represented by my sister Brenda. Waterford International Brigader Frank Edwards is represented tonight by his son Seán. Belfast Brigader Gerry Doran will be represented tomorrow by his daughter Anne, who is travelling over from Glasgow with other family members. The last commander of the International Brigade’s British Battalion, Manchester-Irishman Sam Wild, is represented here by his daughter Hilary, while fellow Manchester Brigader Sid Booth will be represented tomorrow by his daughter Pat. Also present on behalf of the IBMT are our Secretary Marlene Sidaway, partner of the late Brigader David Marshall, and our Treasurer Pauline Fraser, daughter of Brigader Harry Fraser.

Friends, my purpose here tonight is to give you an insight into some of the key issues that motivated a variety of Irish International Brigaders to fight for the Spanish Republic. More of the historical backdrop to that conflict will be given in this Church tomorrow by Harry Owens in his lecture on the Spanish War itself. I will therefore restrict myself to these basic facts. In February 1936 the people of Spain voted into office a liberal democratic Government, giving the parties of the Popular Front 269 seats, an absolute majority of the total of 480 seats in the Spanish Parliament. In July 1936 General Franco launched an armed rebellion against the Spanish people’s democratic choice, and in this he was assisted, from the word go, by the armed forces of Hitler’s Germany and Mussolini’s Italy. International Brigaders from across the world, among them 300 Irishmen, rallied in turn to defend the Spanish Republic against the forces of European Fascism.

This stand required an unusual degree of moral courage on the part of such Irishmen, for public opinion in their own country was very much against them. Religious hysteria was worked up to such a pitch that the Irish Fascist leader Eoin O’Duffy even raised a volunteer force of 700 to fight against the Spanish Republic on behalf of Franco, although they quickly returned home again with little stomach for that conflict. But the Irishmen who volunteered to defend the Republic were to stay on to the very last Battle of the Ebro. And they were often made painfully aware of how their very own families did not necessarily understand why they had taken the stand they did. In 1979 my father published the first edition of his book “Connolly Column – the Story of the Irishmen who Fought for the Spanish Republic”: It carried the following dedication which tells us so much. He wrote: “To the memory of my father who, because of the propaganda against the Spanish Republic in Ireland, did not agree with my going to Spain, but who disagreed more with our ‘coming back and leaving your commander, Frank Ryan behind!’” And his mother’s even more intensely felt religious allegiances would have led her to be all the more receptive to clericalist propaganda against the cause for which her son had taken such a courageous stand, which must have rendered all the more painful the manner in which a message from him was to be delivered to her. When my father was wounded in the Battle of the Ebro he sent a telegram home to his mother to reassure her that he would pull through. And the post office employee delivering that telegram, not content with rudely thrusting it at my grandmother, venomously added the following curse:

“It’s dead he should be, for fighting against Christ!”

The atmosphere among the Irish Catholic emigrant community in Glasgow was not very different from that in Ireland itself. Geraldine Abrahams, daughter of Gerry Doran, has written of him as follows:

“On 14th December 1936, he was one of the 14 Irishmen who crossed the border from France into Spain, led by Frank Ryan. Ten days later, on Christmas Eve 1936, he fought at the Battle of Lopera in Córdoba, where he sustained severe head and arm injuries. A French doctor at the field hospital saved his life and he spent the next six months in Spain recovering from his injuries. Tragically, six of the men who had crossed the border into Spain with him on the night of 14th December lost their lives at Lopera, two of them 17 years old.”

“Like so many other volunteers, Dad hadn’t told his mother he was going to Spain. He wrote to her in April 1937 from Albacete where he was recovering from injuries. He talked of those young men: ‘Well mother, I don’t know what way you judge my action in coming out to Spain, but even now I am more convinced than ever that I did the only thing worth doing – helping to kill fascism before it spread to my own country. Some of the best of Irish lads have fought and died in their efforts to save democracy – Tony Fox, only 17 years old, Kit Conway, the finest type of soldier I have yet met, Dinny Coady, Mick Nolan, Mick May. They had no regrets, as their deaths each resemble a nail in the coffin of international fascism and of O’Duffy’s and his hirelings’.”

Geraldine continues:

“His mother was not the only person he hadn’t told about going to Spain. His then fiancée Kay (our mother) broke off the engagement as soon as she heard he had gone. However, she eventually relented and forgave him, and they were married in 1940. Those people in the IBMT who knew our mother will recall that she became a great supporter of the organisation in the last few years of her life, but in those early years she had a very different view. Back then, she thought our father had gone out on the wrong side and discouraged any talk about Spain in front of us children – my sister Anne and me.”

The sheer viciousness of the propaganda and hatred faced by those Irish who took such a courageous stand against Fascism in Spain was summed up in a series of articles that ran all week in the “Irish Independent” in the New Year of 1937 and concluded with the following Fascist curse pronounced on those International Brigaders from Ireland who would meet their deaths, beginning with the Achill Islander Tommy Patten in December 1936 and ending with Jack Nalty and Liam McGregor in September 1938. I quote: “In concluding these articles, I wish to state that the present Government of Madrid is 100% Red and violently opposed to the Catholic Church. Any Irishman preparing to fight for or defend vicariously this regime is defending the enemy of his faith.”

As for those who volunteered to go to Spain to fight, the wording of the plaque being unveiled here this weekend is broad enough to encompass both strong and weak, because we know what it cost each and every one of them to take the stand they did. It is dedicated to all those volunteers prepared to take such a stand against Fascism. But we in the IBMT are also pleased to note that this very wording is unequivocally solid enough to exclude any honours for the type of man who claimed to have been the very first Irish volunteer – Charlie McGuinness of Derry – and who initially did go out to Spain, but when offered the opportunity to actually fight for the Republic, he promptly returned home in December 1936 and during that very month, while the first Irish International Brigaders were already being killed in action, he commenced his production of such scurrilous, but all too influential, Fascist propaganda for the “Irish Independent”.

Yes indeed, it was none other than the same Charlie McGuinness who had been the author of that Fascist curse on the heroic dead that I have just quoted. But we ourselves intend to honour those heroes, to mention just two of them named in Christy Moore’s song, “Viva la Quince Brigada!”:

“Bob Hilliard was a Church of Ireland pastor

From Killarney across the Pyrenees he came

From Derry came a brave young Christian Brother

Side by side they fought and died in Spain.”

Éamon McGrotty was that Derryman’s name. I remember accompanying his late brother John, in both 1994 and 1996, to the mass grave of 5,000 where Éamon is buried near Jarama; how John brought clay from their parents’ grave to mix into that mass grave and brought some of Jarama’s clay back to their grave; how he carried his brother Éamon’s own missal with him on both occasions; and how he retold the double hurt experienced by his family when they sought to have a Mass said after Éamon’s death in February 1937 and the Bishop of Derry refused them, saying that a Mass would be no benefit whatsoever to Éamon, as he was “now in Hell”. McGuinness’s dirty work had borne fruit.

The International Brigade drew volunteers from both North and South. In the North they came from both the Catholic and Protestant communities, from political traditions that were variously Republican or Unionist, Communist or Independent Labour. The volunteers who hailed from the South were all Irish Republicans in the Wolfe Tone tradition – Catholic, Protestant, Jewish and atheist. I will name but a few. Bill Scott from a Dublin Protestant working class tradition that had seen his father fight as a member of the Irish Citizen Army alongside his leader James Connolly in the 1916 Rising. Frank Edwards – a Waterford teacher already victimised by the Christian Brothers when sacked from Mount Sion School in 1935 – who, on his return from Spain, found himself blacklisted by Catholic schools for his Spanish Republicanism and by Protestant schools for his Irish Republicanism, but who also found that the one and only school prepared to employ him was Dublin’s Jewish National School.

Frank had been born in Belfast in 1907 to a Catholic family that was subsequently forced out of its home by sectarian conflict and then settled in Waterford. On the outbreak of World War One, Frank’s father enlisted in the British Army and perished during the course of that war. Frank’s elder brother Jack took a different course. He was the chief organiser in Waterford of the one-day general strike in April 1918 that prevented the British Government from imposing military conscription on Ireland. He subsequently fought in the Irish War of Independence and took the Republican side in the Treaty War that followed. He was captured by Free State Government troops in mid-July 1922. What next happened to his brother Jack was to leave a deep and lasting impression on Frank Edwards, as he himself would recount: “He was taken to Kilkenny Jail where, after a few weeks, he was shot dead by a sentry on the 19th of August. It was known to be a reprisal for the shooting of a Free State officer in Waterford. Someone called Jack to the window of his cell. A sentry had his rifle pointed and fired it. ‘Shot while attempting to escape’, they said, but we knew differently. I went to Kilkenny to claim his body.” Seán Edwards, with us here tonight, is in fact named for his Uncle Jack.

Another volunteer, originally from Kerry but for a number of years intimately linked with Belfast as a Church of Ireland clergyman, was the Reverend Robert M. Hilliard, who was to fall at Jarama in February 1937. He had been born in Killarney in 1903, son of a successful leather merchant, and entered Trinity College Dublin at the age of 17. His late nephew, the Reverend Stephen Hilliard, following in his uncle’s footsteps as both Socialist Republican and Church of Ireland clergyman, wrote the following of Robert’s early years:

“At Trinity he was noted for his Republican politics, being a member of the Thomas Davis Society … On at least one occasion, while home on holidays from college, he fed the local IRA men downstairs in the kitchen of the family home in Killarney, leaving his nervous parents upstairs with strict instructions not to come down while he was entertaining these particular visitors!”

Bob Hilliard himself would in fact join the IRA during the Treaty War, resulting, not unsurprisingly, in his expulsion from Trinity. He would, however, later return there to study Divinity. He was involved in two revivals of the Trinity College Hurling Club, in 1922 and 1931, and he himself actually hurled for the team during both periods. But it was as a boxer that Hilliard first became best known, being Irish bantamweight champion in both 1923 and 1924, and going on to represent Ireland at the 1924 Olympics in Paris. In 1930 Hilliard returned to boxing again, becoming Irish featherweight champion in 1931.

By this stage Bob Hilliard’s nickname was that of “the Fighting Parson”, as he had by now become a Church of Ireland pastor. He had also moved North in his ministry. In 1931 he served as curate in Christ Church, Derriaghy, and in 1972 that Church was presented with a communion chalice, paten and cruet in his memory by a fellow International Brigader, Joe Boyd, who was himself an agnostic. After he had been appointed to the Belfast Cathedral Mission in 1933, Hilliard became greatly radicalised by the social upheavals in that city during this period. Personal problems saw him subsequently leave for London, where he became even more radicalised in later years, volunteering for Spain in December 1936.

Hilliard’s last message to his family was dated 24th January 1937 – a fortnight before his death. Let me quote from that farewell:

“My dear, Five minutes ago I got your letter. There is a ‘Daily Worker’ delegation here who will take this back. They leave in ten minutes so I have time for no more than a card which will have an English postmark. Teach the kids to stand for democracy. Thanks for the parcels, I expect they have been forwarded to me, but posts are held up very long & especially parcels. Do not worry too much about me, I expect I shall be quite safe. I think I am going to make quite a good soldier. I still hate fighting but this time it has to be done, unless fascism is beaten in Spain & in the world it means war and hell for our kids. All the time when I am thinking of you & the children I am glad I have come. Give my love to Tim, Deirdre, Davnet & Kit. Write when you can, it will help. Love to you, Robert.”

Bob Hilliard also wrote to a friend:

"We came from France in motor lorries. Spirits were high. Speaking one to another we said ‘Franco has heard we are coming, already he is on the run.’ In the morning we were in the barracks at Figueras .The commandant arrived and we were given the choice of a day’s rest or of moving on. Unanimously we voted to move. Four hours sleep and breakfast. Then the train to Barcelona. We marched through Barcelona. What a march! Everywhere the people were out to salute – the clenched-fist anti-fascist salute, but in particular I remember one woman. She was about four feet in height, she wore a brown shawl with a design at the border – a shawl very like what an Irish woman from the country wears in town on market days. She carried a basket on her left arm, but her right arm was raised and her hand clenched in the anti-fascist salute. Her face though was what mattered. Her hair was black, her forehead wrinkled and heavy lines marked the sides of her mouth. She stood to attention as we passed, nearly two hundred of us marching in fours, and her mouth was moving rapidly up and down, holding back the tears. She was a brave old lady. Who knows whom she had lost in the fight against fascism?”

When I first had the opportunity of meeting Bob Hilliard’s daughter Deirdre in March 2005 she was carrying both of these items of her father’s correspondence with her.

The Gospel says:

“So shall the first be last and the last be first. For many are called but few are chosen.”

We have already seen how the man who claimed to have been the very first Irish Volunteer in Spain, Charlie McGuinness, rejected that call as soon as he could and dishonoured himself by immediately going into the service of Fascism before the end of 1936.

But tonight we will honour by name the very last International Brigade volunteer from Ireland who joined in May 1938 – a man who saw no conflict between his anti-Fascism and remaining true to his Catholic faith throughout the whole course of his life. That man was an Ulsterman – James Patrick Haughey from Lurgan, Co. Armagh – who fought shoulder-to-shoulder with both my own father and Jack Jones in the Battle of the Ebro during July and August 1938; and who was captured and imprisoned that September, ending up where Bob Doyle had already been imprisoned for the previous six months – in the Fascist concentration camp of San Pedro de Cardeña. Haughey was to continue his struggle against Fascism as a member of the Canadian Air Force during the Second World War.

As with the letters of the Reverend Bob Hilliard, the following letter written from Canada after Haughey’s release from that Fascist Hell brings us still closer to the great humanity of all such volunteers.

This letter from Jim to his sister Veronica is dated 25th May 1939:

“My dear Sis,

You can’t tell how delighted I was to receive your letter this evening. Although it made me kind of homesick, it’s nice to know that some people at home have not forgotten me, and I intend to do a lot of writing tonight …”

“I arrived in Spain on the 13th of May 1938 and after I had been there for a few weeks I had to go to a hospital with malaria. I had a pretty tough constitution then so I was fully recovered within 20 days. Then I went up to the front. Our battalion went into the line 700 strong, 50 odd returned. We were in the trenches for 63 days without rest. God, Veronica, it was terrible. We had only rifles and machine-guns against hundreds of German and Italian aviation, tanks, artillery and Italian and Moorish troops. In this battle, the battle of the Ebro, Franco had more than 100,000 casualties while we had 40,000. I had umpteen narrow escapes from death which would take too long to describe. I was blown up 4 times, had my shirt and pants ripped to pieces with machine-gun bullets and was lost for three days in no-man’s-land without food or water. This may seem fantastic, but it’s true. On the twenty-fourth of September our company was in a position on the top of a small hill. I was in command of about thirty men, the total remains of two companies (full strength, 150 men to a company). I saw that we were completely surrounded by the enemy, we had only rifles and a few revolvers so we couldn’t put up any resistance. (By the way, I was a confirmed sergeant at this time, and discovered since, that on the day I was captured my lieutenant papers came through. Lieutenant Jim Haughey, how does it look, pretty good, eh? Age doesn’t matter in the trenches). Well, we were finally captured, by this time only 8 of us were left. The captain of the bunch that captured us ordered his men to shoot us. Our hands were tied and a bandage placed over our eyes. This I refused in the good old traditional style. While our grave was being dug I asked this Captain would it be possible to see a priest as I was Catholic. As he was a Catholic himself he said yes, after some conference with his superiors. This saved our lives as it was taken for granted that my fellow-prisoners were Catholics also. But he was so enraged because we wouldn’t snivel or whine for mercy that he bent a colt .45 over my head. I lost all interest in the proceedings for a few hours after that. It would be impossible to describe the humiliations we suffered after that until we arrived in the concentration camp. Here we met some more international prisoners of war. There were 36 different nationalities, including Irish, British and Americans … Here I had my head dressed and settled down patiently to await the day when we should be liberated. There were 400 of us in a room which would hold 50 comfortably, no smokes, no books, 1 toilet and one water tap for 400 men, abundance of lice, very little food, beans twice a day. For the last 3 months before we were released we were fed on bread and water, nothing else. “

“Here there were some Basque and Asturian priests. In one part of this 200 year-old building there were some nuns prisoners also. There are several hundred priests and nuns in Franco’s prisons because they want to tell the truth about this ‘saviour of Christianity’ who is merely the tool of Hitler. I hope and pray that some day the truth will come out about this, Veronica dear, it would take hours to describe all I have seen and experienced in Spain. I also wrote about 20 letters home while I was in prison. You can guess what happened to them …”

“Give my regards to everyone … I pray for you all every night and ask Mummy to watch over you and take care of you. I hope and trust that you don’t forget me in your prayers.

Your affectionate brother,

Ex-lieutenant Jim

P.S. This letter contains some things that sound as if I am drawing on my imagination, but every word is absolutely the truth.”

Jim Haughey was to be killed in a plane crash on 12th September 1943. On 31st October 1943 “The Times” of London posthumously published Jim’s poem – simply entitled “Fighter Pilot” – over the name of Séamus Haughey. These verses have echoes of the WB Yeats poem “An Irish Airman Foresees his Death”, but possess the greater authenticity of being the actual premonitions of a real airman, rather than Yeats’s attribution of his own imagined thoughts to Robert Gregory.

“I think that it will come, somewhen, somewhere

In shattering crash, or roaring sheet of flame;

In the green-blanket sea, choking for air,

Amid the bubbles transient as my name.

Sometimes a second’s throw decides the game,

Winner takes all, and there is no re-play,

Indifferent earth and sky breathe on the same,

I scatter my last chips, and go my way.

The years I might have had I throw away;

They only lead to Winter’s barren pain.

Their loss must bring no tears from those who stay,

For Spring, however spent, comes not again.

When peace descends once more like gentle rain,

Mention my name in passing, if you must,

As one who knew the terms – slay or be slain,

And thought the bargain was both good and just.”

Tonight we do more than mention his name in passing. And, of course, we particularly recall the name of a neighbour’s son, George Brown. And this brings me back to my last meeting with Evelyn Jones, when both she and Jack attended the 1991 Delegate Conference of the Irish Congress of Trade Unions in Killarney. During a break in proceedings, I drove Jack and Evelyn out to the Co. Kerry village of Kilgarvan, birthplace of International Brigader Michael Lehane, who was later killed by a Nazi German torpedo during World War Two, while serving with the Norwegian Merchant Navy.

As we paid silent tribute at the Lehane memorial that had been unveiled by my own father two years previously, it was a particularly poignant moment for Evelyn. For Mick Lehane had fought side by side with both of her husbands – with George at the Battle of Brunete and with Jack at the Battle of the Ebro. As we drove on towards Kenmare and took the mountain road back to Killarney, I informed Evelyn that, in August 1989, Annette’s uncle, Luke Hennessy of Glensensaw, had brought me to see the actual birthplace of George Brown. We had walked up a country boreen [or maybe, speaking here tonight, I should use the South Kilkenny dialect of Irish and say “bosheen”!], situated just outside the neighbouring village of Ballyneale, to see the ruins of the original Lackey home. Afterwards, Luke also introduced me to a member of the Lackey family still living in the Ballyneale area. Evelyn was indeed very much delighted to hear that George’s name continued to be remembered in his birthplace.

George Brown’s mother, Mary Lackey, hailed from Ballyneale, while his father, Francis Brown, was a blacksmith from Inistioge. Although both were Irish emigrants who had married and settled in Manchester, Mary decided to return home to Ballyneale for the birth of each of her first four children. It was here that her fourth child, George Brown, was born on 5th November 1906. George was educated, earned his living and was politically active in Manchester, where he was primarily in the public eye as Manchester Organiser of the Communist Party of Great Britain. But a poem written nine years after his death also speaks of him as a fighter for Irish freedom. For George proudly retained his Irish identity, enthusiastically participating not only in the Céilí dances of Manchester’s Irish Clubs but in their political activities as well.

As a young teenager during Ireland’s War of Independence George, through his family ties, would have remained very much aware of how that War unfolded in his native county. There will indeed be more than an element of poetic justice involved tomorrow when George Brown will be honoured high up above us here at the Olive Grove Memorial to Kilkenny’s International Brigaders in Woodstock Gardens. We might even call it an act of Republican reclamation! For, during the War of Independence, Inistioge’s Woodstock House, with its commanding views of the surrounding countryside, was the headquarters for the whole of the South-East region of Ireland of Britain’s Army of Terror, the RIC Auxiliaries. So bad was their behaviour that their first commanding officer, Brigadier General Crozier, resigned in protest at their ever-escalating atrocities, and he would later accuse the British Government of trying to impose Fascism in Ireland. And yet the people of South Kilkenny defied those Woodstock Auxies. A few miles downstream from here, by the River Nore itself at Glensensaw, Annette’s grandfather, Martin Hennessy, risked everything right under the very noses of the Auxies, as he provided a safe-house, not only for his fellow Kilkenny members of the IRA, but also for national leaders like Dan Breen and Liam Lynch. And it was, beyond the shadow of a doubt, very much a case of risking everything, as the Auxie torture chambers of Woodstock House could have testified. Hennessy family childhood memories well recalled the moment of sheer terror as the bayonets of a military search-party prodded haystacks, but mercifully not the precise haystacks where IRA volunteers were indeed hiding!

It was also a first cousin of Martin Hennessy’s mother, the Thomastown hurler Nick Mullins, who, along with his fellow South Kilkenny volunteer Sean Hartley of Glenmore, would be the very last Kilkennyman to fall during our War of Independence, when killed in action at the June 1921 Coolbawn ambush that was fought out in the North Kilkenny coalfields of Castlecomer. This weekend the traditions of both North and South Kilkenny are once again brought together as we commemorate this county’s four International Brigaders – the two Castlecomer mineworkers, Seán Dowling and Michael Brennan, and the two Ballyneale brothers, Michael and George Brown.

Let us never forget what Woodstock House stood for during that period, as this region’s “Black-and-Tan” citadel, and let us never forget how their terror trampled in particular on the democratic rights of the people of this immediate locality. In December 1920 Richard O’Keeffe, with an address at Woodstock, Inistioge, was sentenced by a court martial to six months in prison. Not for involvement in any violent affray, armed or otherwise; not for the possession of a gun, nor even a single bullet; but for the possession of a notebook – if he even “possessed” that! And what was the supposed “war crime” contained in that notebook? It was an oath of allegiance to the First Dáil – the very first Irish Parliament to be democratically elected by the Irish people themselves. [This “conviction” was officially reported as follows, in the “Irish Times” of 18th December 1920: “The following results of courtsmartial trials are forwarded for publication: Richard O’Keeffe of Woodstock, Co. Kilkenny, was charged before a district court-martial held in Cork. The evidence showed that outside the house of the accused was found a notebook, containing the oath of allegiance to Dáil Éireann. The accused was sentenced to imprisonment for six months, without hard labour.”]

Just as Thomastown’s Nick Mullins had given his life in order to defend the democratic will of the Irish people, as expressed in the General Election of December 1918, so seventeen years later would his neighbour’s child, George Brown, give his life in order to defend the democratic will of the Spanish people, as expressed in their General Election of February 1936.

How would George Brown himself have turned out if economic circumstances had not forced his parents, Mary Lackey and Francis Brown, to emigrate to Manchester? Being from Ballyneale, he might very well have hurled locally for Tullagher and “let it rip!” [“Let it rip, Tullagher!” is the “war cry” of Tullagher Hurling Club]. Indeed, he might even have made it to the county team, like his kinsman Eddie Keher. For sport was certainly in his genes. In Manchester George himself actively competed in track and field athletics. He also boxed, swam and rowed. Only ten days before his death, he wrote the following from Spain on 27th June 1937 to his friend Mick Jenkins [who, during the 1970s, would author that pioneering biographical study, simply entitled “George Brown – Portrait of a Communist Leader”]:

“We have held joint concerts within the Battalion, football matches and boxing tournaments. By the way, the boxing tournament was held in the local bull ring and during one of the more scientific contests when little blood flowed, one of our ‘warriors’ was horrified to overhear a young girl say to her friend that it was not as exciting as bullfighting. The next contest was a needle match between two strong armed merchants. You should have heard the crowd then! I’d have been sorry for any poor bull that strolled in at that time. The Spanish lads are great football players and our lads have all their work cut out when opposing them.”

But George Brown was primarily anxious to play his full part in the field of battle itself, and he did so at Brunete in July 1937. Let me quote from the diary kept during that battle by the Waterford International Brigader, Peter O’Connor:

“June 30: At 9pm received the order to ‘stand to’.

July 1: ‘Standing to!’ Paddy Power left for home at 12.30 this morning. I feel very lonely after Paddy as we had been in several battles together. (I would like to state here, that this is the eve of the Great Republican Offensive of the Brunete Front. There were three brothers, Johnny, Paddy and Willie Power, in the Irish section)…

July 4: Left for the front….

July 6: Attack started at 5.00am. Fascists in rout at 9.00am.

July 7: Mick Kelly killed. Advancing steadily, took the village of Villanueva de la Cañada.

July 9: Fascist counter-attack today. Got as far as our lines but driven back with heavy losses on both sides. Johnny Power and Paul Burns wounded, both in the legs. Our Battalion Commander Law killed. Our great Spanish comrade Humanes was also killed besides many other comrades. Just heard of the death of George Brown, our great comrade of the British Communist Party.

July 14: I feel very lonely now as I am the only Irishman left in the line. The rest being either wounded or killed.”

Sam Wild also recorded:

‘I’ll be seeing you soon’ said George Brown, when he was seeing a bunch of us off in December of 1936. About three weeks later great excitement prevailed amongst the Mancunians in the village where we were training – Manchester’s latest contribution to our Battalion had arrived in the shape of its District Organiser. We kept him busy telling us all the latest from Manchester, as if we’d been away for years … In July, when we moved up for the first big offensive, the Republican Government launched the battle of Brunete. I was disturbed in the middle of the night by a group of comrades shouting for rifles, gas masks and ammunition. I was serving as Battalion Armourer at the time and George was one of the group who wanted fixing up. While I was rigging them out, George told me he had asked to be allowed to join the Battalion as a soldier. ‘After all, that’s what I came out for’. He said in reply to my bantering.”

“Midnight, 6th July, found George moving up with the Battalion towards its first objective, the town of Villanueva de la Cañada, a highly fortified position surrounded by trenches and well placed machine gun nests. It was during the attacks on this town that George was killed. He died as he lived, in the vanguard of the fight against Fascism and reaction.”

The circumstances of George Brown’s death were as follows:

His unit was met by an advancing group of civilians, including women and children, from the village of Villanueva de la Cañada. Not knowing that these civilians had guns to their backs and were being used by a party of Fascist troops behind, the International Brigaders were subject to surprise attack. And as he lay wounded on the road, George Brown was knifed to death by a Fascist.

Evelyn told me how, even in old age, George’s mother, Mary Lackey, walked with a remarkably straight and upright back. This, she explained to Evelyn, was from the manner in which, as a child in Ballyneale, she had carried water from the well on her head, an image we might now only associate with Africa. On George’s death Mary Lackey said: “I am proud of my son and the only thing that is keeping me up is that he died for the cause of freedom and anti-Fascism, in which he believe till his last breath.”

Several decades after his death a unique handwritten manuscript was to be deposited in the Working Class Movement Library in Salford. It was the text of a poem written in honour of George Brown. Its author is unknown and, while no date of composition is given, the reference to nine years after his death suggests 1946. An excerpt was published in 2006 in “Poems from Spain: British and Irish International Brigaders on the Spanish Civil War”, edited by Jim Jump, but it has never been published in full. The following, then, is the full text of that anonymous poem, kindly sent to me by Jim Jump himself, who is also editor of our IBMT Newsletter:

IN MEMORIAM GEORGE BROWN

(author unknown)

Now you are asked to go away from yourselves,

Away from the street of your life,

From the houses and the rooms of your lives.

Leave behind the voices of your children,

Leave behind the smoke of your chimneys:

Leave it behind:

You are asked to be in another place at another time

To yield yourselves to this journey,

To another sun and to other shadows;

Going from the safe to the unknown,

From the clanging of your tramways

To a distant silence,

From to-day to yesterday

And to a day which has not yet come.

You, you, looking at me, looking at yourselves, wondering:

Man next to man,

Woman next to woman:

You are changed now, changed,

Come away, come away.

This is to-day: a bad day, a day of dying.

And a good day when life

Is given a push to live more swiftly

More lively!

To-day it is very hot.

The heat is on your lips, on your tongues…

To the north – look closely! Brunete.

Nearer, nearer, a cluster of white houses, open; Villanueva de la Cañada.

There are parched fields, some trees, a road, telegraph poles,

Dust and thirst and a surge.

This is Spain. The white houses

Are Spain’s white houses

On the crossroads in Spain.

The fields are Spanish fields

The telegraph lines run

To Ávila and Segovia.

The serge is the old serge

The same surge, the new surge,

To grow, to break out, to be free,

To be more happy, to live.

Up the road lorries move, carefully.

In extended order, through the dry fields men go, slowly.

What do they carry?

Rifles.

The sun burns their shoulders.

Earlier there was the roaring of guns,

But now they are stilled.

You, you are going forward.

Forward, forward, adelante, adelante!

Your faith is no longer

In your hands, in your heart, on your lips:

It is in your fingers, in your stomach, in your aching feet.

How hot this day is, those white – white houses!

And who is the next man, the man next to you?

Staring ahead at the white houses of Villanueva?

This one, yes, this one…

He turns his face, his eyes – yes.

George Brown.

George Brown goes no longer there.

No good looking – he’s no longer there.

George Brown is no longer George Brown, he is dead.

He was killed by the fascists in Spain.

At the little village

Of Villanueva de la Cañada

On the sixth of July

Nineteen-thirty-seven,

Aged twenty-nine years.

They killed him.

His head and his hand,

His flesh and his bones

And the strength and the love in them

Was buried in Madrid.

We know who George Brown was:

A worker, an organiser,

A fighter for Ireland’s freedom.

A leader of the workless,

A communist. A soldier:

Now a dead man in Spain.

We know where he was born,

We know where he played.

Perhaps whom he loved,

We know how he fought

And we know how he died.

Why go over it?

It is changed now.

Like steam becomes rain,

Like ice becomes water,

Lust becomes life

And thought becomes dead:

So he is changed,

So we are changed.

When George Brown went forward

Towards Villanueva

With the lads of the Fifteenth

International Brigade –

He did not know the people

Who were coming to meet him

On that dust gray road.

And how could he know,

That hidden behind them,

Those brotherly peasants, men, women and children

Who came to surrender or to greet liberation,

Were the enemy soldiers?

Perhaps we shall never know who they were.

What happened eludes us:

What happened after we must remember.

George Brown, he certainly knew this:

That the past and the present

Are a meal for the future.

If you were to search

By Villanueva de la Cañada

The spot where they slew him,

You should probably find

That the scattered houses

Have new roofs and chimneys.

The ravaged fields

Have nine times grown wheat.

’Tis nine years ago

That George Brown was killed.

A little of him

Has got into the stones,

Has got into the wheat,

Has got into the land.

To-day the red sun

Is still burning down

Onto the fields

Where we tried to burst

The ring around Madrid.

The sun beats down

Not onto a memory, but onto a sorrow:

It warms and it ripens

The fever, the restlessness,

the anger and the hope,

In the heart of Spain

And in our hearts.

There is George Brown –

There he goes, undying –

He turns his face, his eyes –

Hello! George Brown.

Irish and English, past and memories,

Strikes and hunger marches,

To fight and to wait;

Yes, and the earlier

Dreams and awakenings,

All has been melted down

In a greater longing.

Now that is given up,

Now that you lost it,

Now it must become

Mankind’s belonging.

They say that nothing rhymes

On the name: Manchester.

I say Brunete is a rhyme

For every city:

That’s where the past was made

That’s where our doubts must fade

Our fears and our pity.

Where shall we find you, George Brown?

We shall find you laughing in the mountains of Guadarrama

When we come back.

We shall find you at Teruel

When there’s dancing in the streets.

We shall find you again in the streets of Madrid,

When Manchester and Brunete

And Villanueva de la Cañada have become

One and the same.

We shall come again, lorry after lorry, man after man,

In extended order, marching forward,

To find you where we left you,

Always George Brown.

Glory! What a day that’ll be,

Wonderful, glorious,

What a day of wonder!

Every man will be a poet then

And every poet be free of his poetry;

Finding no song is made

For such a morning!

Come back and look around.

One man is missing,

He did not return from the journey with you.

He, and many as he,

Have stayed behind.

They did not come home.

To the clanging of trams in Mosley Street,

To the rain-swept pavements of Piccadilly.

They have been changed for us.

And we, we are changing,

Let us remember: nothing stands still.

Only for a brief moment

May we recapture what they were,

The gestures of their hands,

Their jokes, their short caresses.

Everything moves, we must be the movers.

Everything changes, we must be the changers.

Surely and certainly:

Our day is coming.

Now he and they,

Are only a breath in the wind,

Only a rippling on the water,

A bone in Spain.

But every part

Is driving to the whole,

The child is turning over,

Ready to be born.

The breath of the wind

Will become a storm,

The rippling on the water,

Must become a tidal wave.

He and they and us:

We will break through.

Don’t mourn them –

Who would be mourning

When a star breaks from a star?

That is how planets,

How new worlds,

Are made.

But of course, George Brown was greatly mourned. And it would be four decades after his death before the new planet of the Spanish democracy for which he had given his life would again see the light of day. We can, however, truly rejoice that in 1996 Spanish democracy recognised just how much it owed to George Brown and his comrades, when the Spanish Parliament unanimously agreed to confer the right to be given Spanish citizenship on all surviving International Brigaders, among them Jack Jones and Bob Doyle. And with this weekend of commemoration we can also rejoice at the fact that, little more than a week short of the 71st anniversary of his death, the spirit of George Brown has at long last returned to his native Kilkenny.

When the Dublin-born writer [and future member of the French Resistance] Samuel Beckett was asked where he stood on the Spanish Civil War that was then raging, his reply was short and to the point, but also so very evocative of our own War of Independence [in which his own aunt, Cissie Beckett, had participated]. Writing it all as one word, but in capital letters, Beckett simply proclaimed:

UPTHEREPUBLIC!

So I will conclude with these very few words in both Spanish and Irish:

BIENVENIDO A CASA, GEORGE BROWN!

Y VIVA LA REPÚBLICA!

FÁILTE THAR NAIS ABHAILE, A SHEOIRSE DE BRÚN!

AN PHOBLACHT ABÚ!

END

The Chairman, Joe Doyle, then called on the President of the International Brigade Memorial Trust, Jack Jones, to propose the vote of thanks to the lecturer. Jack had been born in Liverpool in 1913 and named James Larkin Jones, in honour of Big Jim Larkin, founder of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (now SIPTU) in 1909. Jack’s docker father had in fact been a good friend of Larkin’s when the latter also worked on the Liverpool docks in the years prior to his departure for Ireland in 1907. In 1921 Ernest Bevin was to bring about a number of union mergers that led to the formation of Britain’s Transport and General Workers’ Union (now UNITE), and Jack James Larkin Jones would himself go on to become the TGWU’s most outstanding post-war General Secretary from 1969 to 1978. Jack Jones was, of course, also an International Brigade volunteer who was wounded while fighting in the 1938 Battle of the Ebro, the last battle in which the International Brigades would take part. Later that year, he would marry Evelyn, widow of George Brown, and they would share sixty years of love and common struggle together.

Jack Jones proposed a vote of thanks to Manus O’Riordan for a lecture that had brought the story of George Brown alive in his birthplace. George Brown himself had been engaged in the work of organising the unorganised and Jack Jones also stressed the importance of organising. He concluded by emphasising the lessons of working class unity in the 1930s which now needed to be learned once more for the struggles ahead.

EVENTS OF SATURDAY, 28TH JUNE 2008

On the following morning, again in St. Mary’s Church, a lecture on the Spanish Civil War itself was given by Harry Owens. Harry was also responsible for mounting the photographic exhibition by Pablo Vazquez Borraga, simply entitled “Defenders of the Spanish Republic”, that was on display in the church entrance during the course of both days of commemoration.

The Chairman for this session was Jack O’Connor, General President of SIPTU. He spoke of how great an honour it was to be in the presence of his own great trade union hero, Jack Jones. He introduced Harry Owens as another person with a strong background of trade union struggle, arising from his employment as a night telephonist. But Harry Owens must be particularly praised for his work in pioneering International Brigade commemorative events in Ireland. It was Harry who organised a major international conference in Dublin in 1986 to mark the 50th anniversary of the Spanish Civil War. It was also to Harry Owens that credit was primarily due for the Dublin Council of Trade Unions initiative which resulted in the unveiling in 1991 of a Memorial Plaque to all of the Irish International Brigade dead at SIPTU Headquarters in Liberty Hall. Harry had also edited Bob Doyle’s memoirs for publication in two languages: as “Memorias de un rebelde sin pausa” in Spanish in 2002, and “Brigadista” in English in 2006.

Harry Owens next proceeded to give such a powerful and vivid narrative of so many aspects of the Spanish Civil War that, upon its conclusion, his lecture evoked a prolonged standing ovation from his Inistioge audience.

Harry’s lecture was then followed by presentations to both Jack Jones and Bob Doyle, of an autographed hurley stick each, together with a sliotar (ball), by Kilkenny’s outstanding hurling star and six times All Ireland champion, Eddie Keher. A first cousin once removed of George Brown (on the Brown side of the family), Eddie Keher spoke of how the foundation of the Gaelic Athletic Association, and its promotion of both Gaelic football and hurling, had itself been a blow against national oppression, as George Brown, Jack Jones and Bob Doyle had struggled against oppression internationally. Jack Jones again spoke of how much loved and respected George Brown had been and how powerfully his cherished memory had lived on in his and Evelyn’s home. He would ensure that this Kilkenny hurley would now be proudly displayed in George’s memory at his union headquarters in London’s Transport House.

Paddy Murphy (Pádraig Ó Murchú), Chairman of the Inistioge Memorial Committee, presented a George Brown commemorative plaque to Jack O’Connor, who said that this also would have in honoured place in Dublin’s Liberty Hall. The Chairperson of UNITE, Tony Woodhouse, then presented commemorative plaques to two cousins of George Brown, Mrs. Eily O’Brien (neé Keher) and Mrs. Mary Doolin (neé Keher), as well as to Bob Doyle and Jack Jones.

On the conclusion of these memorial proceedings in St. Mary’s Church, the commemoration then moved to the adjoining graveyard for the unveiling by Jack Jones of the Memorial Plaque, worded as follows:

WE SALUTE THE MEMORY OF

GEORGE BROWN

SON OF INISTIOGE

BORN IN BALLYNEALE ON 5/11/1906

MANCHESTER WORKING CLASS ACTIVIST

AND MEMBER OF THE XV INTERNATIONAL

BRIGADE IN THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR.

HE LOST HIS LIFE AT THE BATTLE OF

BRUNETE ON JULY 7TH 1937

IN DEFENCE OF THE SPANISH REPUBLIC

This graveyard ceremony was presided over by Waterford playwright Jim Nolan. The introduction and keynote address was given by Seán Walsh, Secretary of the Inistioge George Brown Memorial Committee. The oration was delivered by Jimmy Kelly, Irish Regional Secretary and Assistant General Secretary of UNITE.

“Where shall we find you George Brown?” was recited by Sarah Tobin, a relation of George Brown (on the Lackey side). Marlene Sidaway, Secretary of the International Brigade Memorial Trust, read the speech that “la Pasionaria”, Dolores Ibarruri, had delivered at the farewell parade of the International Brigades in Barcelona on 27th October 1938, when she declared:

“You can go proudly. You are history! You are legend! You are the heroic example of democracy’s solidarity and universality … We shall not forget you and, when the olive tree of peace is in flower … return!”

At the graveyard ceremony IBMT executive members Hilary Jones, Pauline Fraser, Marlene Sidaway and Manus O’Riordan carried the Memorial Banners of both the British Battalion and the Connolly Column, 15 Brigada Internacional. The Graiguenamanagh Brass Band, augmented by former members of Inistioge’s own St. Colmcille Brass Band (among whose founders had been a grandfather of George Brown), played the anthem of George Brown’s own County Kilkenny, “The Rose of Mooncoin”, the IBMT anthem, “There’ a Valley in Spain called Jarama”, and the International Brigades anthem, “The Internationale”.

The attendance next proceeded to Woodstock Gardens for a tree planting ceremony to mark the occasion of the visit by Jack Jones and his family to Inistioge. This ceremony was presided over by Sean Kelly of UNITE, who had worked tirelessly as the Commemoration Project Co-ordinator. Jack Jones himself planted the tree on behalf of his and Evelyn’s family. Manus O’Riordan read out the roll of honour of all those Irishmen who had given their lives in defence of the Spanish Republic, while Spanish historian Lidia Bocanegra thanked International Brigaders on behalf of democratic Spain’s new generations.

At the Woodstock Gardens Olive Grove Memorial to Kilkenny’s International Brigaders, a presentation of a life-long achievement award to the George Brown Memorial Committee Chairman Paddy Murphy, in recognition of his promotion of the commemoration of George Brown over a 50 year period, was made by his life long friend and comrade Seán Garland. A further presentation was made by Andy McGuinness of SIPTU, in recognition of Paddy Murphy’s lifelong activist service in the Federation of Rural Workers component of SIPTU.

Inistioge’s “Hatchery Folk Group”, led by Terry Bannon, provided a musical tribute, which included Christy Moore’s song “Viva la Quince Brigada!”, sung with two additional verses in memory of George Brown that had been written by James “Shamur” Kelly. A recital on the Irish harp was performed by Brenda O’Riordan, which included “Marbhna Luimnighe” (“Limerick’s Lamentation”), the lament which she had played at the May 2006 funeral of her father, International Brigades veteran and “Connolly Column” author Michael O’Riordan, and which had also been played on the pipes at both the June 1979 Dublin reburial of the remains of Irish International Brigade leader Frank Ryan and at the October 2005 IBMT Frank Ryan Commemoration.

The attendance then returned to Inistioge, where the Brass Band again played on the Village Square that same anthem with which Frank Ryan had rallied the International Brigades at the Battle of Jarama – “The Internationale”:

“Then comrades come rally

And the last fight let us face.

The Internationale

Unites the human race!”

END

See http://www.rte.ie/news/2008/0628/6news.html for

“Spanish War hero remembered” on RTE TV News on June 28

– incl. Inistioge interview with Jack Jones on George Brown.

See http://www.geocities.com/irelandscw/ibvol-GBComm.htm for the ”Ireland and the Spanish Civil War” website coverage of the George Brown Commemoration

© Manus O’Riordan